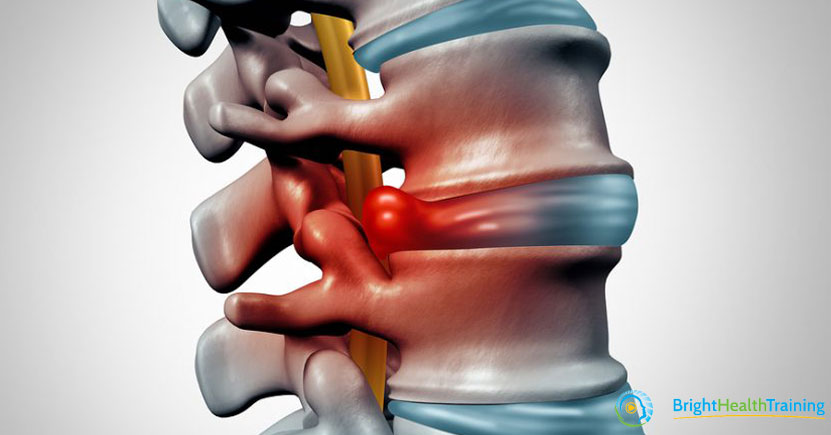

The Jelly Donut Theory

The Jelly Donut theory suggests that your vertebral discs behave like jelly donuts. If you flex forward you can squirt (bulge) the “jelly” (nucleus pulposus) out the back of your disc (annulus fibrosus) in disc related injuries. This is the logic why you shouldn’t flex your spine too much, that flexion pain is most likely disc pain and extension pain is most likely of facet joint origin.

Well as tasty as it sounds, it looks like this Jelly Donut (theory) might actually be disproved.

A review of 4 different studies on the behaviour of our “jelly donuts” (intervertebral discs) show that old understandings of disc behaviour are basically wrong. Here are some of the reasons why:

1. Until very recently we couldn’t even see intervertebral discs on imaging (1990s was when MRI became more common), most of the theories around disc bulges were created even earlier than the 1960s.

2. The concept of “jelly” is a very poor analogy for the nucleus pulposus, because:

“adopting different postures deforms the nucleus pulposus and therefore, changes the position of the nucleus pulposus but there is no apparent nucleus pulposus migration within the intervertebral disc.” Nazari et al 2012. In other words, the “jelly” changes shape when you move, but it doesn’t move forward or backwards within the disc.

3. One (thesis) study did show “movement” of the nucleus pulposus, (but read point 4 to understand why its not really moving).

…”between group comparisons identified that the asymptomatic subjects also demonstrated significantly greater posterior sagittal plane NP (nucleus pulposus) migration than the DLBP (discogenic lower back pain) subjects.”

In other words, the jelly “moved” in healthy, pain-free spines, but barely moved in the painful spines. So the idea the “jelly” squirts out in painful backs, is unlikely. Alexander, L 2014

4. With spinal movements it’s not actually the nucleus pulposus that moves, but more the disc itself, the annulus fibrosus (the “donut”). A much more thorough investigation of disc movement showed during extension:

“NP (nucleus pulposus) margins remained unchanged relative to the vertebral body but moved anteriorly with respect to the IVD (Inter Vertebral Disc).” Kim et al 2017.

So its more the case the donut moves around the jelly, at least in healthy spines.

5. It’s actually very possible that the discs themselves actually bulge anteriorly in flexion and posteriorly in extension.

Anterior and posterior IVD margins moved posteriorly with respect to the vertebral body in extension. Kim et al 2017

6. The final word actually goes way back to 2000. This summary of intervertebral disc findings by Edmonston et al (2000).

Lumbar spine position was found to be associated with small measured changes in anterior disc height and nucleus position, however, this response was variable within and between individuals. The theoretical concept of a stereotypical effect of spinal position on the lumbar IVD is challenged by these initial data. Since the health of the disc is often unknown in clinical practice, manual therapy treatment for lumbar spine pain should be based on the symptomatic response to movement and position rather than biomechanical theory.

Discogenic back pain is very real, but before you next start talking about discs as the cause of your clients or patients back pain, please keep this in mind; Most low back pain is non-specific (commonly cited as 90%)… In the previously mentioned Australian study (1172 patients with acute low back pain in primary care) fewer than 1% had specific causes for their pain.

Maher et al. published in the Lancet, 2017.

Take Home Message

Please be very careful when making assumptions around the drivers of pain. Especially when it comes to discs and backs. At one time, discogenic pain was the hot new topic in back pain care, and we can still see the echoes of that today. Literature around backs and discs are everywhere, hence why the term “slipped a disc” is a household term. But please understand concepts such as the jelly donut theory were developed before we had the capacity to be able to see inside human bodies while they are moving, at least without some level of torture involved.

Instead, it is much more statistically correct to assume a client’s spine is healthy and functional but if they are obviously in pain, you need to treat each person individually and holistically and avoid jumping to conclusions. Listen – let the client tell their story and then you can help in a way that is specific to them. Don’t buy those jelly donuts.

References:

Maher et al, 2017 Non-specific Low Back, Lancet Vol 389 No. 10070 pp 736-747

Nazari, J. et al 2012 Reality about migration of the nucleus pulposus within the intervertebral disc with changing postures Clinical Biomechanics Vol 27 No 3 pp 213-217

ALEXANDER, L. A., 2014. The effect of position on the lumbar intervertebral disc. Available from OpenAIR@RGU. [online]. Available from: http://openair.rgu.ac.uk

Kim, Y.H., et al 2017 Effects of Cervical Extension on Deformation of Intervertebral Disk and Migration of Nucleus Pulposus PM&R Vol 9 No.4 pp 429-338

Edmonston, S.J., 2000 MRI evaluation of lumbar spine flexion and extension in asymptomatic individuals

Manual Therapy Vol 5 No.3 pp 158-164